Or is it?

How you answer that question will likely define how you feel about this novel. Answer one way, and "The Goldfinch" is an overwrought, cliched orphan's tale with unearned artistic pretenses, as some critics have argued. Answer it another way, and you have--well, a Pulitzer Prize winner.

So why two starkly different responses? The reason is baked in. At its heart, "The Goldfinch" is an orphan's tale. Its strengths and its weaknesses stem from that fact.

When Theo loses his mother at 13, Tartt builds her narrative on the classic orphan protagonist trope that has thrived from Oliver Twist to Harry Potter. The formula is relatively simple: Take one plucky child hero who's lost everything and set him adrift amid unfeeling adults who have anything but his best interests at heart.

In Theo's case this means first being raised by the snobbish Park Avenue Barbours, who constantly make him feel unwelcome, before being tossed into a crumbling Las Vegas suburb with a deadbeat gambling father and a drug-addicted cocktail waitress. (We even get the next two important pieces of the formula early on, the sage-like kindly caretaker/guide, Hobie, and the lovably disreputable sidekick, Boris.)

Theo is easy to root for from the onset, but that's also the problem. He's a little too easy root for. It's not that good literature needs a flawed hero. Theo is actually plenty flawed. The problem is how overly flawed nearly every adult in the novel is. From Park Avenue to Las Vegas, Theo might as well be living at 4 Privet Drive no matter what his address. Even Hobie and Theo's mother have histories so scarred by parental figures acting horribly that, as these accounts of unfeeling adults pile up, they can't help but stretch credulity.

My point here calls to mind Ruth Graham's controversial Slate critique of young-adult literature "Against YA." What separates young-adult (YA) literature from adult literature, Graham argues is often the narrow perspective of the child or teen narrator:

"But crucially, YA books present the teenage perspective in a fundamentally uncritical way. It’s not simply that YA readers are asked to immerse themselves in a character’s emotional life—that’s the trick of so much great fiction—but that they are asked to abandon the mature insights into that perspective that they (supposedly) have acquired as adults."

"The Goldfinch" can't help but fall into this trap even though Theo is narrating the childhood portion of his story years later in his 20s. Something about the way nearly every adult character is flattened into villainous one-dimensionality made me wonder at times what the real difference was between this novel and YA literature.

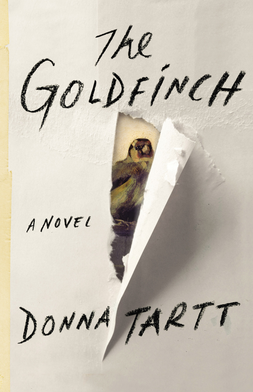

Yet I think this narrow perspective is also essential to making the novel compelling, and there is, of course, one major aspect of the novel that clearly separates Theo Drecker from Harry Potter--The Goldfinch. When Theo walks off with the Carel Fabritius painting after escaping the bombing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Tartt creates a macguffin that not only carries along the narrative thread but also elevates the novel.

Though there were times I found it difficult to accept that Theo would continue to hide the painting from everyone around him for so long, I enjoyed the added narrative weight and artistic resonance it provided. At times it seems tangled with his survivor's guilt, his love for his mother, his suicidal thoughts, the secret shame of his unreasonable crush on Pippa, but always it is a simple object of extreme beauty.

And this is where "The Goldfinch" gets its literary cred, as the novel resolves with a stirring statement on the value of beauty and artifice:

"Whatever teaches us to talk to ourselves is important: whatever teaches us to sing ourselves out of despair. But the painting has also taught me that we can speak to each other across time. And I feel I have something very serious and urgent to say to you, my non-existent reader, and I feel I should say it as urgently as if I were standing in the room with you. That life—whatever else it is—is short. That fate is cruel but maybe not random. That Nature (meaning Death) always wins but that doesn’t mean we have to bow and grovel to it. That maybe even if we’re not always so glad to be here, it’s our task to immerse ourselves anyway: wade straight through it, right through the cesspool, while keeping eyes and hearts open. And in the midst of our dying, as we rise from the organic and sink back ignominiously into the organic, it is a glory and a privilege to love what Death doesn’t touch. For if disaster and oblivion have followed this painting down through time—so too has love. Insofar as it is immortal (and it is) I have a small, bright, immutable part in that immortality. It exists; and it keeps on existing. And I add my own love to the history of people who have loved beautiful things, and looked out for them, and pulled them from the fire, and sought them when they were lost, and tried to preserve them and save them while passing them along literally from hand to hand, singing out brilliantly from the wreck of time to the next generation of lovers, and the next.”

Though some critics have argued that these last lines feel overly "told" and are unearned by the rest of the novel, I have to say I fell for it. I can appreciate the disconnect critics point out, and I have trouble with the ways the book glosses over issues of addiction, depression, class, and gender.

But when I hit this last line, I felt transported. Up to this point the narrative made me care and pulled me along effectively--though at times a little guiltily. Then this ending made it all feel somehow larger than it was. What more can you ask for from literature? Sure, this could be a trick, low-brow fiction coming to the high-brow party in a knock-off designer gown, but for me at least, it pulled it off.

No comments:

Post a Comment